The United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) propose a simple, powerful idea: that a collective blueprint is necessary to achieve a more just and sustainable future for all. Despite the monumental challenges faced by our global society—including the existential threat of climate change; the concentration of wealth and power; rising violence and discrimination against the poor, communities of color, LGBTQIA+/Two-Spirited, and religious minorities; suppression of the rights of tribal nations and stateless persons, the brutality of state violence and the repression of democratic rights—Echoing Green believes that through a collective pursuit of justice, humanity will be able to rectify imbalances of power, cease exploitation, and ensure the rights and dignity of all.

For over 30 years, Echoing Green has supported leaders (“Echoing Green Fellows”) who fight for equity by solving problems on-the-ground and in their communities. We know the importance of investing early in brilliant community innovators—people who see a problem and gather themselves, their networks, and their resources to build toward a solution. The Echoing Green community crosses boundaries built to separate along class, race, gender identity, religious, and geographic lines. This community sees and experiences how the world often falls short of respecting the rights and dignity of humanity but refuses to accept those shortcomings as inevitable.

The Sustainable Development Goals

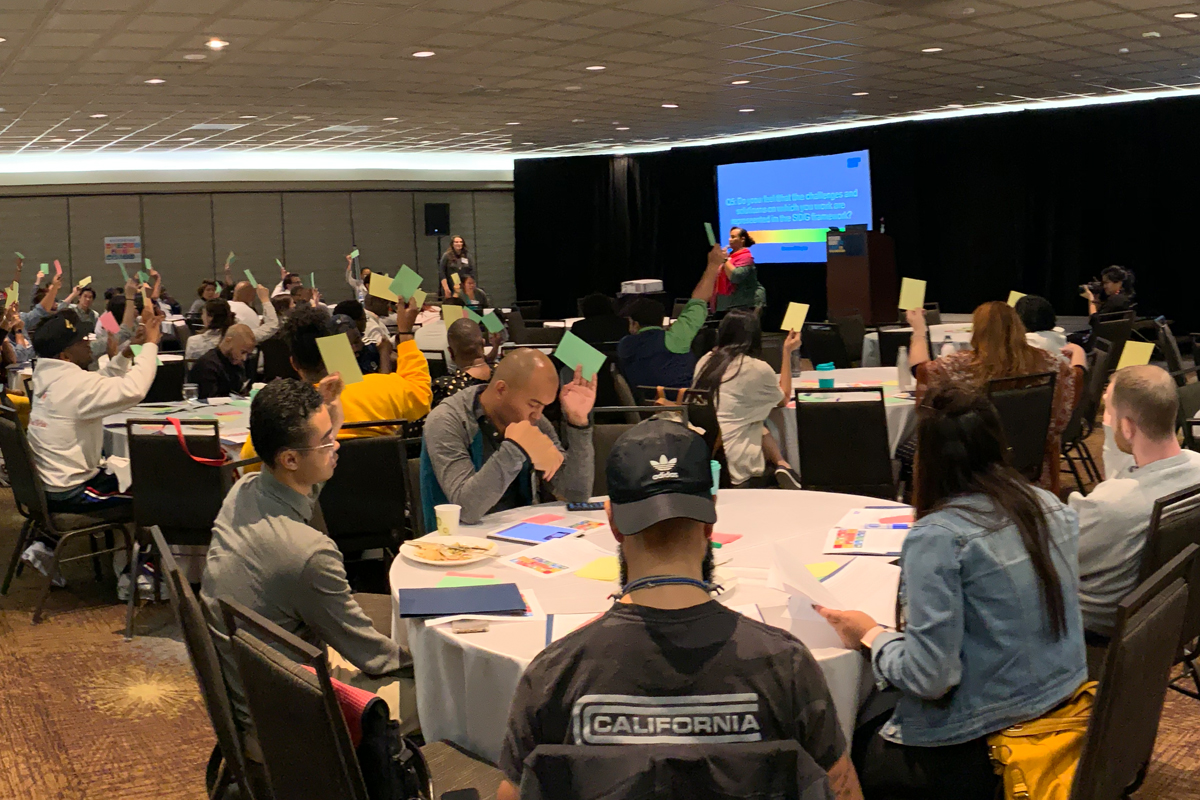

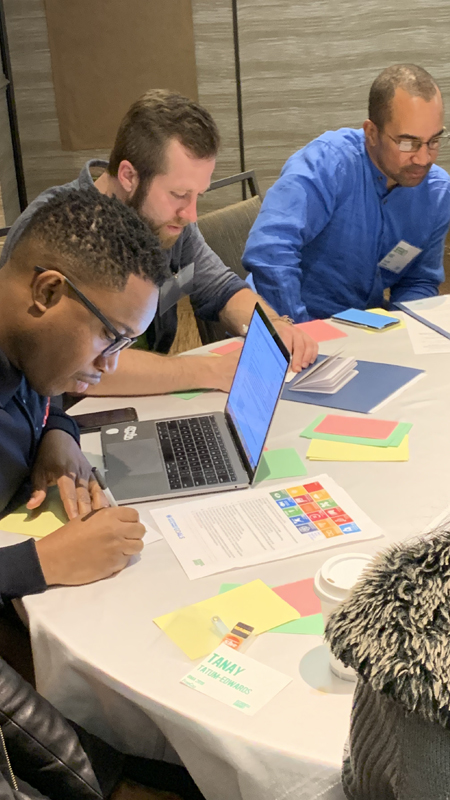

Social innovators are creators and disruptors, but are still drawn to the promise of common frameworks, like the SDGs, as infrastructure for change. In 2018 Echoing Green began discussing our and our Fellows’ work in relation to the SDGs. Echoing Green’s unique perspective within the social entrepreneurship and social innovation field, where leaders are on the front lines of tackling the issues outlined in the SDGs, surfaces ideas and perspectives not discussed in the traditional development conversations. At Echoing Green’s 2019 Summit in Los Angeles, we brought together nearly 150 Fellows from across the world to learn from one another, meet and network with our wider community, and consider their work in the context of three SDGs: Decent Work (SDG 8), Reduced Inequalities (SDG 10), and Climate Action (SDG 13).

While we initiated a discussion of the framework and how it impacted both their individual and collective work, what we heard was a familiar and powerful call: collective action has to be collaboratively designed, with front-line social innovators and community leaders as a central voice in decision-making at the highest levels of political and economic policy. The SDGs are a critical platform for discussing the nature of economic, social, and political power in our world and how inclusivity, equity, and transparency can shift those dynamics.